By Steve Okoekpen –

At the end of 2010, African oil and natural gas reserves were estimated to be between 200 and 210 billion barrels of oil equivalent. The conventional forecasts see African oil supply growth continuing over the next 25 years, and the renewed global scramble for Africa’s more than 25 billion barrels of oil that will become available for export has intensified over the past decade.

Those scrambling to secure and exploit this abundance of fossil fuels include former colonialists and major, energy-hungry economic super powers and emerging economic powers: China, the U.S, E.U, Japan, Brazil, India, Russia and even Turkey.

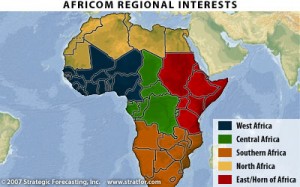

Since the end of the Cold War – and particularly over the past decade – Africa’s status in the international geopolitical order has risen dramatically. The continent was once treated as a convenient battlefield in the global rivalry between the so-called western industrialised nations led by the United States and the Soviet Union precisely because neither superpower had any vital interests at stake on the continent. Now, a number of developments – especially the conflicts and uncertainty in the Middle East and the continent’s increasing importance as a source of energy supplies and other raw materials for industrial growth – have radically altered the picture. They have led to the growing economic and military involvement of China, India, Brazil, Iran and other emerging industrial powers in Africa and to the re-emergence of Russia as an economic and military power on the continent. In response the United States has dramatically increased its military presence in Africa with the creation of a military command – the Africa Command or Africom – to protect what it has defined as its “strategic national interests” in Africa. This has ignited what has come to be known as the “renewed scramble for Africa’s resources” and is transforming the security architecture of Africa.

If Europe provided the scene for the US-Soviet ideological rivalry during the cold war, in recent years Africa has emerged as the arena on which the U.S. and China intend to play out their rivalry over acquisition and/or exploitation of energy resources. For the past 5 decades, the western economic powers led by the U.S., Britain and France controlled Africa’s vast mineral resources through its multi-national oil companies and trading firms with ease and co-operation from the legion of corrupt African leaders and despots.

Over the past decade, having its attention and resources diverted by the global war on terror and conflicts in the Middle East, the US and its partners have now awakened to China’s increasing appetite for African oil resources. The success of China’s energy security strategy has alarmed the US, concerned that it could be losing its leverage in the African region to Beijing’s open cheque book policy. In response the United States has dramatically increased its military presence in Africa through Africom – to protect what it has defined as its “strategic national interests” in Africa.

America noted for its doctrine of military dominance, responded with AFRICOM, which came into effect from September 2008 and now based in Sttugart, Germany. The Command met stiff opposition from some African leaders who believe it will further destabilise a region already prone to civil war. The US has followed such a strategy in the Middle East over the last 50 years in the guise of CENTCOM, with bases at various times in the United Arab Emirates, Kuwait and Saudi Arabia and the Fifth fleet in Bahrain.

However, adopting such a policy has potentially dire consequences for the future energy and national security of the US, with some fearing that it will force the Americans into partnership with unsavoury regimes in the African region. Indeed, the so-called intervention in Libya has left the country in chaos with islamist militias in control and weapons in free flow through Sahara Africa, the French’s intervention in Mali and the insurgence of Boko Haram terrorist group in northern Nigeria and recent efforts to oust Al Shabaab and other islamic fundamentalists from Mogadishu in Somalia and Kenya have, in the process, spread the war on Al-Qaeda onto the African continent, adding to concerns about the US’ new interventionist approach with drone strikes across bases on the continent.

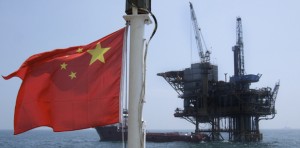

China’s growing investment portfolio and substantial role in oil exploration and production in Africa is often cited as the most important signal of how these new and emerging economic powers are usurping the place of the United States and European countries and threatening to “expel” the West from Africa. Analysts do not believe China will further raise the already high US suspicions of its intentions by contemplating a military presence on the Africa continent.

But China still only gets less than 9% of sub-Saharan Africa’s total oil exports; 32% of Africa’s oil still goes to the United States and 33% still goes to Europe. China does obtain significant amounts of oil from African countries – some 30% of its total imports, primarily from Sudan, Angola, and Nigeria – but it actually gets more of its imported oil from the Middle East, specifically from Saudi Arabia where oil production is dominated by American firms. So the situation is a little more complicated than the picture that is often presented.

By 2006, Africa contributed to 12% of the world’s oil production. By 2010, it was expected to provide as much as 30% and a US Department of Energy study projected that African oil production would rise 91 percent between 2002 and 2025. According to the International Monetary Fund (IMF), in 2006 total gross private capital flows to Africa amounted to $45bn compared to $9bn in 2000. Most of it was concentrated in the extractive industries and an estimated 70% went to oil exporters Nigeria, Angola and Equatorial Guinea.

The US consumes 25% of the world’s oil production. It imports 13.5mn b/d of its daily consumption of 20.6mn barrels. According to the Energy Information Administration’s (EIA) International Energy Outlook (IEO) report, this figure is expected to rise by almost 50% by 2025. At present Africa supplies 15% of the US import needs compared to 22% from the Middle East. Within the next decade Africa’s share is predicted to increase to one-quarter of US total oil imports.

Oil from West Africa’s Gulf of Guinea region provides an ideal source of supply for the US, given the high grade of the crude and the closer geographical proximity of the mainly offshore fields than Middle East oil. In addition – with the exception of Nigeria (which once threatened to pull out) and Angola – African producers are not members of OPEC and, given the poor state of their economies, offer easier investment facilities than elsewhere.

The US Gulf of Guinea oil strategy began due to domestic pressure to diversify supplies away from the Middle East in 2003 under the Pan Sahel Initiative (PSI), which was designed to provide anti-terrorism training but was in reality fuelled by the substantive oil discoveries in the region. The Gulf is believed to hold potential reserves of 60bn barrels of high quality, relatively low cost oil. In this decade the Council on Foreign Relations estimates $50bn will be invested in the Gulf’s energy sector, with US companies accounting for 40% of it.

Nigeria, which holds about 60% of the Gulf of Guinea’s oil wealth, is one of the top 3 biggest sources of oil imports to the US. It is the cornerstone of US strategy in the region and thus the reason behind America’s renewed interest in Nigeria. However, the US saw this strategy challenged when former Nigerian President Yar’ adua awarded lucrative oil blocks to Chinese firms instead of America’s ExxonMobil and recently when China sold military equipment to Nigeria to protect oil installations in the Niger Delta region when US deliveries of equipment were delayed.

One reason for America’s continuing interest in basing AFRICOM in Sao Tome and Principe – a Portuguese-speaking island nation in the Gulf of Guinea is because of its very close proximity to Nigeria.

Chinese energy security policy

China currently produces 3.8mn b/d of oil and imports about 40% of its oil needs. No longer self-sufficient since 1993, the Chinese leadership considers its energy supplies to be increasingly insecure and long-time spans are required for its Russian and Central Asian investments to bear fruit. Added to this is China’s continued exclusion from the western economic bloc’s controlled IEA’s emergency cover during supply disruptions.

With domestic production expected to remain largely flat, China may need to import as much as 60% or more of its oil consumption by 2020. As a result, China has been looking to invest in places where oil assets have not been tied down by western oil companies, or places where they can’t go because of sanctions imposed by their governments or are deterred from going by the high risks involved.

US commentators have criticised China for politicising energy security issues in Africa, a criticism which the Chinese have also levelled at the Americans.

But according to analysts, given that the western powers have gained control over the best oil fields available and, as a late entrant to the international oil game, China has little choice but to get oil from wherever it can using whatever diplomatic tools it has at its disposal – particularly so since the Chinese leaderships’ legitimacy rests on its ability to deliver economic growth and maintain social stability. Over the last two decades economic growth in China has averaged about 9% per year and is forecast to continue at this rate for another 20 years.

China is currently Africa’s largest trading partner, surpassing the United States and its traditional European partners. Commercial ties between the two regions exploded since 2000, leaping from $10bn to over $100bn in the last decade.

The towering new African Union headquarters in Addis Ababa was a largely welcomed $200m gift from Beijing and a clear testimony of China’s intention, and ability, to engage with individual states as well as an entire continent, presenting it with new opportunities and challenges.

More than 800 Chinese companies now operate in Africa, mostly as contractors on Chinese projects. One reason for China’s success in Africa has been its ability to integrate private and public initiatives. A good example was in September 2006, when CNPC – which already holds oil exploration licenses in the country – signed what was claimed to be the largest foreign investment project in Chad. The project involves the construction of Chad’s first oil refinery and a cement plant, as well as new roads, a school and a hospital and, at a later date, a pipeline between Chad and Sudan that would increase the volume of oil supplied to the refinery.

Unfortunately, Sudan originally became an issue in Sino-American relations because of Sudan’s civil war and its poor record on human rights. China is one of Sudan’s most important suppliers of military equipment, which Khartoum can easily purchase using revenue from the oil that China helped develop. Sudan used this weaponry against the forces in southern Sudan, which had the sympathy if not outright support of Washington. This dilemma ended in 2005 following a peace agreement, which the United States helped to broker and China welcomed, between northern and southern Sudan. Oil played a critical role in the Sudanese civil war and genocide which eventually led to the partitioning of the country into Northern and Southern Sudan supervised by the two superpowers – China and US.

In a speech made to the China Institute of International Studies in August 2006, Lord Malloch Brown of the British Foreign Office claimed that the massive trade surplus China now has with the US and Europe has led to an imperative for sovereign funds to be recycled – and a significant part of that has gone into investment in Africa. In the first nine months of 2006, for example, China invested more in infrastructure than did the whole OECD added together. The same story goes for trade too, he said. According to the World Bank, the Chinese EXIM Bank has $13bn tied up with infrastructure projects in Africa.

Furthermore, according to the President of the African Development Bank, between 2007-2010 it committed a further $20bn. This is the magnitude of financial commitments that the west has to compete with. If the US views China’s foray into Africa with alarm, the World Bank sees it as a positive force for the continent’s development.

In 2001 China imported oil mainly from the Middle East (56%), followed by Africa (23%). By 2004, Africa’s share had increased to 28% with Angola, Sudan and the Republic of Congo among its top ten suppliers. Since 2004 the number of China’s African suppliers has increased to include Equatorial Guinea, Gabon, Nigeria, Chad and Cameroon. By 2006, Angola had become the biggest oil supplier to China (18.2%), outdoing Saudi Arabia (16.2%). China has now displaced the US as Angola’s biggest customer. In the first eight months of 2007, China’s oil imports increased 15% over the same period in 2006, with Africa supplying 26%.

An advantage China has in the African oil race is that it is willing to invest in war-torn, high-risk countries and allow its state-sponsored oil companies to invest at a loss. This was most recently exemplified by CNOOC and its partner China International Oil and Gas’ agreement with the interim government of Somalia – a country which has been blacklisted by the west. China is taking very high risks- not just because of the uncertain prospects of the interim government, but also because there are doubts as to whether Somalia has any oil at all. The EIA, for one, believes that the country has no proven oil reserves.

Fuelling the Africa oil race alarm

China’s strategy of owning energy resources at source has fuelled alarmists in the US that it intends to direct supplies to its own market and further increase oil prices as there are not enough reserves to meet the demands of other countries. A recent report by the US Congressional Research Service invalidates this notion, but China provides a convenient scapegoat for the US failure to reduce dependence on oil imports and institute structural economic reforms.

In response, the US under President Obama’s energy security strategy increased its focus on United States energy independence. Thus, gas production from tight sandstone reservoirs made up 26 percent of US gas production in 2010. Production from shales made up another 23 percent of US gas production, so that massive hydraulic fracturing made possible 49 percent of US gas production in 2010. Increased US production resulted in decreased natural gas imports: in 2012, the US imported 32% less natural gas than it had in in 2007. In 2013, the EIA projected that imports will continue to shrink due to increases in tight gas and shale gas, and the US will become a net exporter of natural gas around 2020.

Proponents of hydraulic fracturing touted its potential to make the United States the world’s largest oil producer and make it an energy leader, a feat it achieved in November 2012 having already surpassed Russia as the world’s leading gas producer. In 2012, the International Energy Agency (IEA) projected that the United States will see such an increase in oil from shales that the US will become the world’s top oil producer by 2020. In 2011 the US became the world’s leading producer of natural gas when it out produced Russia. In October 2013, The US Energy Information Administration projected that the US had surpassed Saudi Arabia to become the world’s leading oil producer as well.

So far, the flow of oil from China’s equity oil acquisitions has been very modest. More than 90% of its imports do not originate from its equity oil projects. The EIA reports that in 2006 only 320,000 b/d of China’s 3.6mn b/d of oil imports was equity oil. So, China still has to rely on the international market for a large part of its oil imports.

According to Nicholas Shaxson, author of a book about oil in Africa – entitled Poisoned Wells – and an associate fellow at Chatham House in London, too much is often made of China’s investment and acquisitions in Africa. So far they are mostly smaller acquisitions, he says, compared to the US, British and French oil companies which have been investing over a longer term in larger fields and on a much bigger scale.

ExxonMobil, an American oil company for example, sources 30% of its global liquid production in Africa. Moreover, not all of China’s investments may pay off the dividends it expects if the current situation in Chad is anything to go by. There, ExxonMobil’s 30-year Doba basin project has unexpectedly peaked within 18 months of its start-up and is currently running 30% below forecast. The quality of the oil is poor and the geology of the oil-bearing structures difficult. Canada’s EnCana, whose interests in Chad were bought out by China estimated the probability of commercial hydrocarbon flows at only 15% to 30%.

China’s threat to US energy security is also exaggerated as, although PetroChina overtook ExxonMobil as the world’s biggest energy company, at least on paper, US oil companies remain the world’s biggest in reserves and most technologically advanced. Furthermore, with the US expected to consume twice as much oil as China by 2030, the US is likely to remain the leading player in the international energy market.

Another thorny issue with the US anti-China lobby is that while oil imports are the most important contributor to the US trade deficit, China’s current account surplus has grown with the rising oil prices. In examining the macroeconomic effect of an increase in world oil prices of $10 and $25, Sano Zaouli, an economist at the University of Paris X11, finds that given its large dependence on oil imports, surprisingly the Chinese economy is little impacted by the price increases. This, he attributes, to the strong investment and the large flow of foreign capital into the Chinese economy that counterbalances and cushions the negative impact of the oil price hikes.

An analysis of the relative importance of oil imports within the energy mix of each country reveals that in the US, oil is predominantly used as fuel for cars, whereas in China it is used by the industrial sector (manufacturing, agriculture and energy conversion). Simply put, in the US oil imports do not add as much to economic growth as in China; in the US the oil is consumed whilst the Chinese add value to the oil. This means that as long as everyone has to pay the same price for oil, China can afford to pay whatever it takes to secure the oil.

Currently although US-China relations are strained but well-managed, China may well try to take advantage of recent manifestations of US foreign policy weaknesses as evident in the Middle East conflicts, Egypt, Syria, Iranian nuclear programme and around the world. Even though the US expansion of its military projection in Africa is not primarily aimed at China’s growing influence in the region it is likely to further raise the stakes.

However, both the United States and China now depend heavily on Africa for their imported crude oil, and the projections suggest that imports from Africa will only increase in the years ahead. Over the long-term, it is in the interest of both China and the United States to promote political stability, good governance, fewer human rights abuses, and less corruption in African oil producing nations.

Chinese investment in Africa has escalated rapidly over recent years, but what are the implications of China’s foray in the continent. Quite certainly, China is an economic powerhouse with long-term ambitions in Africa. Like Brazil, Russia, India and other emerging economic powers, it is here to stay.

Asking whether China is good or bad for the continent is not only beside the point, it distracts us from more pressing and relevant questions, such as what do African states want to gain from these new partnerships, and what are they doing to achieve this?

Investment and new partnerships welcomed by African governments

I have often heard some argue that China is a 21st Century partner for development and a unique catalyst for growth, but critics fear that China is a new colonial power, plundering Africa’s natural resources and exacerbating existing patterns of corruption and inequality.

Advocates claim that China’s rise has benefited the continent by injecting unprecedented investment, dynamism, and confidence into local markets, generating important gains for local economies. Critics, in contrast, accuse China of violating local laws, depleting the continent’s resources, and taking advantage of corrupt leaders.

Despite mounting criticism and the Western media’s largely negative portrayal of events, reality on the ground reveals that, by and large, both African governments and people welcome investment and new partnerships with the Asian giant. “If you want concrete things you go to China. If you want to engage in endless discussion and discourse you go to the normal traditional donors,” a senior manager from United Nations Economic Commission for Africa put it bluntly’’.

However, these partnerships are not without problems and are far from the shining examples of south-south cooperation Chinese leaders and the media often like to portray. The truth of the matter is, China’s involvement in Africa is not a black and white affair. In fact, most of it has grey areas. China does not operate as a bloc but it is composed of a myriad of private investors, state agencies and hybrid actors that spend more time in Africa competing with one another than worrying about Communist Party slogans.

The Chinese in Africa are not a homogenous and cohesive community organised along nationalistic lines as is commonly perceived by outsiders. In addition, the continent is not one single “actor”. Each African country has its own particular set of engagements with China. While everyone seems to know what China wants from its counterparts, less is said and known about what African countries and its leaders want from China.

Lessons for Africa and which way forward

China has opened up new economic, diplomatic and strategic avenues for African states, but it is ultimately down to Africans, both the people in power and the man on the street, to negotiate on their own terms, identify priorities, and leverage opportunities to further their own interests. Contrary to prevailing views, China is not offering a “model” of development. It has no quick-fix recipe for success. Although China is making it possible for Africans to visit, study and work in China, it is not asking, or requesting, other countries to emulate it or support its values.

Since the 1990s, however, China showed that with clear political goals and strong regulation of foreign investment, it could leverage natural resources and low labour costs to develop its economy. The key was letting people get on with it. It may be too early to call China’s economic miracle a success story, or determine how many African countries are willing, interested or indeed capable of following a similar course, but for the first time since the end of the Cold War people from Algeria to Angola, Chad to Zimbabwe have a genuine alternative to the Western donor bloc.

If there is one thing African states can learn through China, it is how to imagine their own future, explore new possibilities, and engage with the rest of the world while retaining control over the conditions of those engagements.

Steve Okoekpen, examines the renewed scramble for Africa’s oil resources. Reach him at steve.okoekpen@gmail.com