By Richard Nield –

The success of Qatar’s Oryx GTL and Pearl GTL projects has led to a renewed interest in gas-to-liquid (GTL) investments, and the companies behind these plants – Sasol of South Africa and the UK/Dutch Shell Group – are now eyeing new opportunities in markets much further afield.

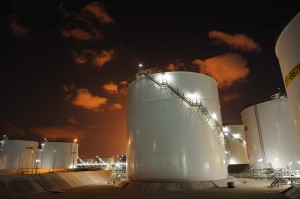

Pearl GTL is the world’s largest source of gas-to-liquids (GTL) products, capable of producing 140,000 barrels of GTL products each day. The plant also produces 120,000 barrels of oil per day of natural gas liquids and ethane.

Production of GTL fuel is nothing new. It dates back to the 1920s, when two German scientists, Franz Fischer and Hans Tropsch, developed a means of making synthetic liquid fuel from the country’s coal stock. The technology, which became known as the Fischer-Tropsch process, converts a synthesised mix of carbon monoxide and hydrogen (known as syngas) into liquid hydrocarbons. This is then cracked to produce fuels such as diesel and kerosene for use in the automotive and aviation sectors, and naphtha, which can be used to produce downstream chemicals.

The early history of GTL was governed by simple economic logic. Production of synthetic fuel in Germany was ramped up significantly during the Second World War and, by 1944, the country had nine plants producing about 14,000 barrels a day (b/d) of GTL products for the war effort. Following the war, Russia lifted one of the plants to set up production of its own, although the plant closed in the 1990s.

The second wave of GTL development was in South Africa, and again the move was moulded by political and economic circumstances. In the 1940s, South Africa had a lack of crude oil and limited means to import it. In order to fuel its automotive sector, it began investigating the use of its own coal resources to produce liquid fuels. In the 1950s, the country’s first GTL plant was established in Sasolburg, with a second following in Secunda. By the 1980s, when apartheid-era sanctions against the government made importing refined products even more difficult, each plant was producing 80,000 b/d of liquid fuels.

Strategic move

The third, and most recent phase of GTL development, has been motivated less by economic necessity and more by the urge of one country to find ways to diversify away from its overwhelming reliance on its huge gas reserves. That country is Qatar, which has the third-largest gas reserves in the world, the fourth-largest gas production and the second-highest exports. It relies on oil and gas for about 50 per cent of gross domestic product (GDP), 85 per cent of export earnings and 70 per cent of government revenue.

Sasol began discussions with Qatar in the mid-1990s for the construction of a GTL plant and, by 2007, the Oryx plant was up and running. Output from the plant, which produces diesel, naphtha and liquefied petroleum gas (LPG), is now at about 32,400 b/d. Oryx was followed in 2011 by the Pearl GTL plant, developed by Shell, which began production in 2011. The Pearl plant produces a mix of diesel, kerosene, base oil, naphtha and paraffin.

Energy efficient

Aside from the strategic rationale behind the development of GTL, the fuel also has several inherent benefits. Chief among them is its low sulphur level, making it cleaner for the environment, and high cetane value (a measure of combustion quality), making it more productive of energy.

But there are also significant challenges to developing GTL facilities, including high start-up costs and sensitivity to the price of oil and gas. “Both the Oryx and Pearl plants had their problems,” says Howard Rogers, director of natural gas research at the Oxford Institute for Energy Studies in the UK. “Oryx was not so bad in retrospect, but Pearl suffered huge cost overruns, largely because it was built during the 2004-09 period when construction costs doubled because of the strain put on the supply chain by development in the BRIC countries, particularly China.

“At the moment, with oil in the region of $110 a barrel, the Oryx plant looks good economically at gas prices of $5 a million BTUs,” says Rogers. “The profitability of the Pearl plant is harder to assess because it’s not possible to strip out the upstream costs from the plant construction costs.”

While Qatar offered the benefits of abundant cheap gas and a government keen to diversify into new products, the search is now on for other locations for the development of GTL production. The US is the focus of much attention because of the dissociation between the oil and gas market. At the moment, the country has the perfect combination of abundant supplies of cheap gas, high liquid fuels demand and high oil prices. Even there, though, project development is taking time.

“It’s a bit of an open question today why we haven’t seen GTL projects move forwards significantly in the US,” says Rogers. “Gas prices are low, at around $3.70-3.80 [a million BTUs], but there’s the obvious question of whether oil prices will stay so high in the future. At the moment, the futures market is in backwardation. So that’s a risk. And then you have the fact that these are very complicated plants. You have to ask whether the costs at the Pearl were due to the complexity, or whether they were just a victim of price inflation at the time. It’s quite daunting for potential investors.”

Russia is another potential location for GTL plants in the future. “There’s quite a lot of talk about GTL projects in Russia, where the domestic gas price is similar to that in the US. On the face of it, you’d expect these projects in the US and Russia to be moving forwards, but the question is whether investors are put off by technical complexity and cost overruns. Exploration and production executives tend to get more excited about finding oil fields or gas fields rather than by converting one to the other. It’s hard to think of a rationale today for converting natural gas into oil based simply on the fact that you can.”

Future projects

Despite the challenges, Shell and Sasol are actively looking to exploit their technological expertise and the experience they have gained in Qatar by developing GTL facilities elsewhere in the world. Sasol is working with the US’ Chevron to build a plant in Nigeria, which is due for completion by the end of 2013. It has also partnered with Malaysia’s Petronas to build a plant in Uzbekistan, for which the front-end engineering and design (feed) is complete.

Shell and Sasol are both looking to develop GTL capacity in North America. Sasol has begun feed studies on a plant in Louisiana, and has carried out a feasibility study for a facility in Canada. Meanwhile, Shell has selected a site for a potential 140,000-b/d facility near Sorrento on the US’ Gulf coast.

But all these schemes are still some way off. Sasol says it will make a final investment decision on its Louisiana facility in the next two years, and whether to start feed studies in Canada within a similar timeframe. Likewise, Shell expects it to be a few years before it makes a decision to go ahead with its proposals.